VISBY MEDICAL™ PATIENT CASE STUDY

A case of undertreatment associated with syndromic management of STIs

Case Study #4: Tina

This study is based on a real-life case.1 Some details have been altered to fit the format of this study to preserve the identity of the patient. All photos are stock photos, used for illustrative purposes only. Posed by models.

Case Intro

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Meet Tina

Tina is a recently married 27-year-old woman who has dreams of having large family and is actively trying to conceive. She presents to the local clinic with complaints of vaginal discharge and irritation.

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Medical and Sexual History

In the exam room, the nurse collects medical and sexual history.2

Tina reiterates her chief complaint as vaginal discharge and irritation, both of which started 1-2 weeks ago. She reports regular menstrual cycles and denies using any method of contraception because she has been actively trying to conceive for the last 12 months.

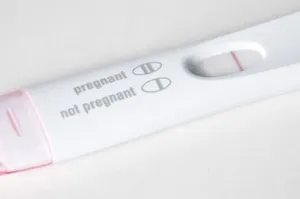

The nurse requests a urine sample to assess for signs of a urinary tract infection and to determine pregnancy status.3

Nurse-patient dialogue

Nurse: When did the vaginal discharge and irritation start?

Tina: I noticed it toward the end of my last menstrual cycle about 2 weeks ago.

Nurse: How would you describe the vaginal discharge and irritation?

Tina: The discharge is more than usual and appears white or off-white in color. The irritation is focused around the vaginal opening.

Nurse: How many sexual partners have you had in the past year?

Tina: I have not had any sexual partners in over 1.5 years beyond my husband. Although we’ve only been married 3 months, we’ve been engaged and trying to conceive for approximately 1 year. In fact, we recently scheduled a consult with a reproductive endocrinologist (RE) since it’s been 12 months without a pregnancy.4

Nurse: Do you or your husband have any history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)? If you used STI prevention methods (e.g., condoms), how often did you use them?

Tina: I’ve never been diagnosed with an STI. My husband has never shared if he has, but I doubt he ever has. I have always used a condom with prior partners and with my husband before we started trying to conceive.

Did you know?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that clinicians routinely obtain a patient’s sexual history as part of an appointment.2 This information helps clinicians determine if the patient has been or is still considered high-risk or at-risk for STIs and/ or engaging in risky sexual behaviors. This information also helps clinicians to counsel patients on risk reduction in the best way possible.2,5 The “Five Ps” approach to obtaining a sexual history consists of key questions used to elicit information regarding the patient’s 5 major areas of sexual health.2,5,6

It is critical that the clinician engages in this conversation with respect, compassion, and a nonjudgmental attitude. Asking open-ended questions can help facilitate the conversation and help build rapport.5

Quiz Question #1

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Physical and Pelvic Exams, Lab Assessments

Tina provides a urine sample for in-house processing. She prepares for the physical and pelvic exam while waiting for the physician.10

Examinations10

Physical Exam

- All vitals are within normal limits

- Patient is alert, well-developed, and well-nourished

Pelvic Exam

External findings:

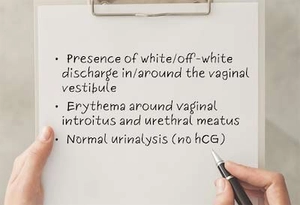

- Noted presence of white/off-white discharge in and around the vaginal vestibule

- Observed mild erythema around the vaginal introitus; patient confirms that is the area in which the irritation is the most notable

Bimanual exam findings:11

- Patient indicates feeling mild tenderness upon palpation of the uterus and adnexal regions as well as mild cervical motion tenderness (CMT)

- No adnexal masses or tubo-ovarian abscesses present

Vaginal swab is collected for lab analysis.1

Laboratory Assessments

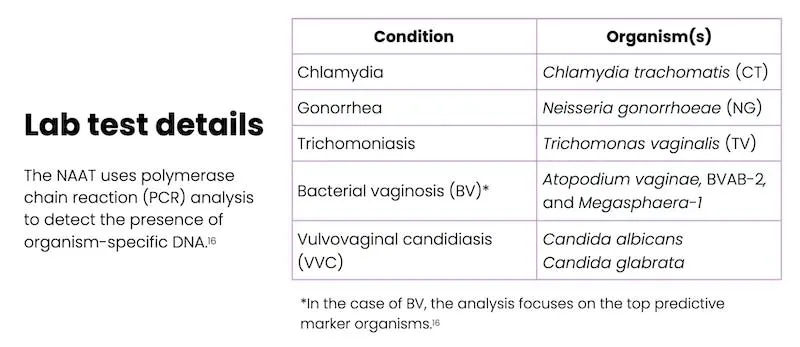

External lab assessments13,16

- Vaginal swab is sent to an external lab for a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) that will test for the presence of organisms that cause conditions suspected in the differential diagnosis (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, BV, and VVC)

In-house urine assessment14

External findings:

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG): not detected; negative15

- Visual assessment: clear, straw-colored

- Chemistry assessment: no protein, glucose, or blood detected

Quiz Question #2

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Treatment Plan

The physician reviews his case notes.

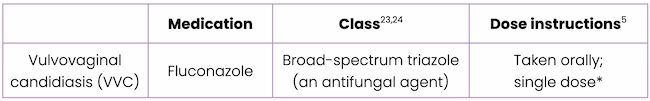

A definitive diagnosis from the lab test will likely not be available for several days, so the physician recommends empirical treatment or syndromic management for VVC.10

*Oral fluconazole treatment is typically administered as a 150-mg single dose for uncomplicated VVC; however, in cases of recurrent or severe VVC, a longer treatment course may be recommended.5

Did you know?

Since Tina is trying to conceive, the physician should consider the drug’s US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling regarding pregnancy and lactation, and the risks associated with certain medications, such as the antifungal agent fluconazole, when taken during conception and early pregnancy. High doses (400-800 mg/day) of fluconazole are not recommended for women who are in their first trimester due to the risk of birth defects. However, the one-time 150-mg fluconazole dose has not been shown to increase this risk. Therefore, the low dose of fluconazole (150 mg) required to treat VVC is still commonly used in women who are trying to conceive or who are in their first trimester of pregnancy because this dose is lower than that needed for other indications.24-26

Syndromic Management

Syndromic management is a strategy used to identify and treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs) based only on the specific presenting syndromes, including symptoms identified by the patient and clinically observed signs of infection.10

- It is utilized widely as a means to medically manage people with symptoms of STIs because untreated STIs can cause serious physical complications (e.g, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and increased susceptibility to HIV and other STIs) and can also impact mental health and relationships with partners.10

- In most resource-limited settings, syndromic management is the standard of care because laboratory diagnosis is not feasible or results from a lab-based test can take many days.10

Key Point

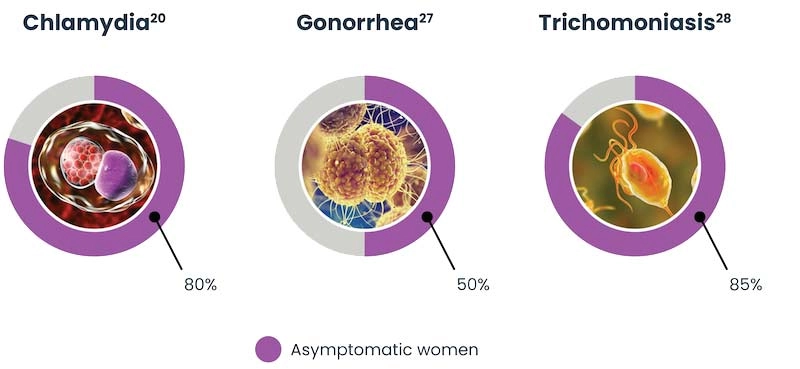

Syndromic management is based on presenting symptoms, but many women with STIs are asymptomatic, including:10

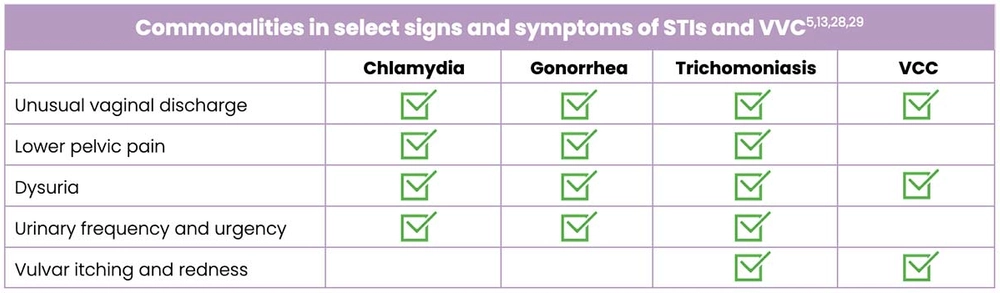

Commonalities

Case Update

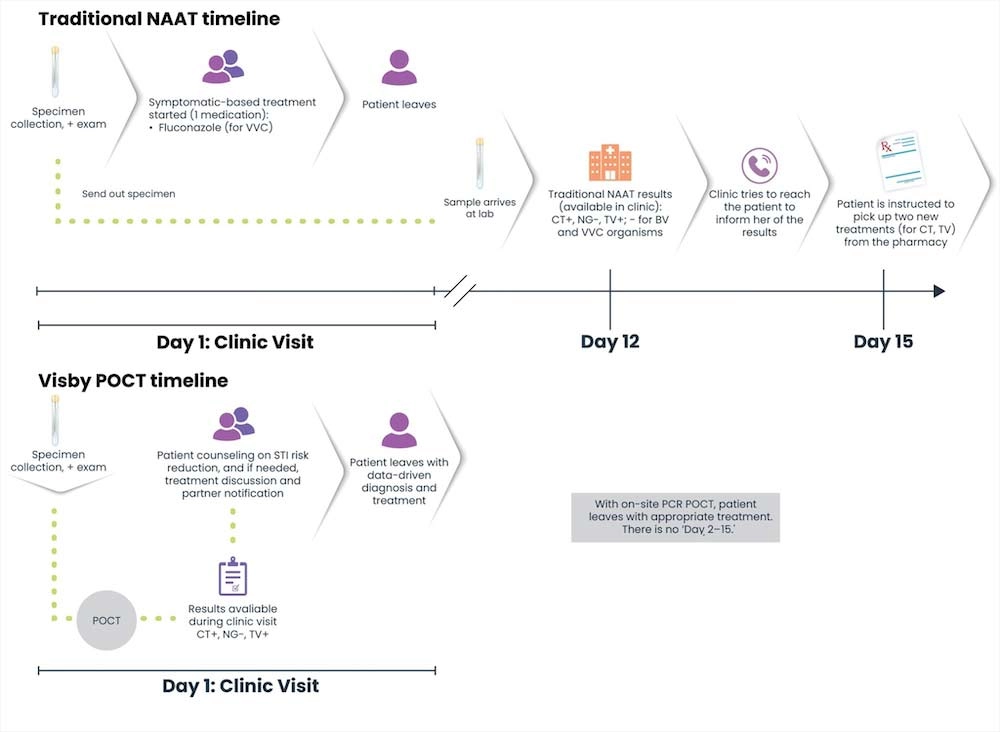

Day 12-15

Day 12

The clinic receives the ST lab results, which have been reviewed by the physician. The results confirm that Tina does not have VVC, but that she does have chlamydia and trichomoniasis.

Day 15

After 3 days and 4 attempts at contacting Tina, the clinic nurse finally reaches her and shares the lab results, which show she has 2 STIs, neither of which were VVC. Therefore, in retrospect, fluconazole was not needed.24

Tina expresses immediate concern that she has contracted these STIs while being in a long-term, committed relationship. The clinic nurse tells her that STIs can often remain asymptomatic and, if left untreated, can persist for several years.30

Tina is instructed to pick up a new prescription for the identified STIs:

- Azithromycin for chlamydia31

- Metronidazole for trichomoniasis32

Key Point

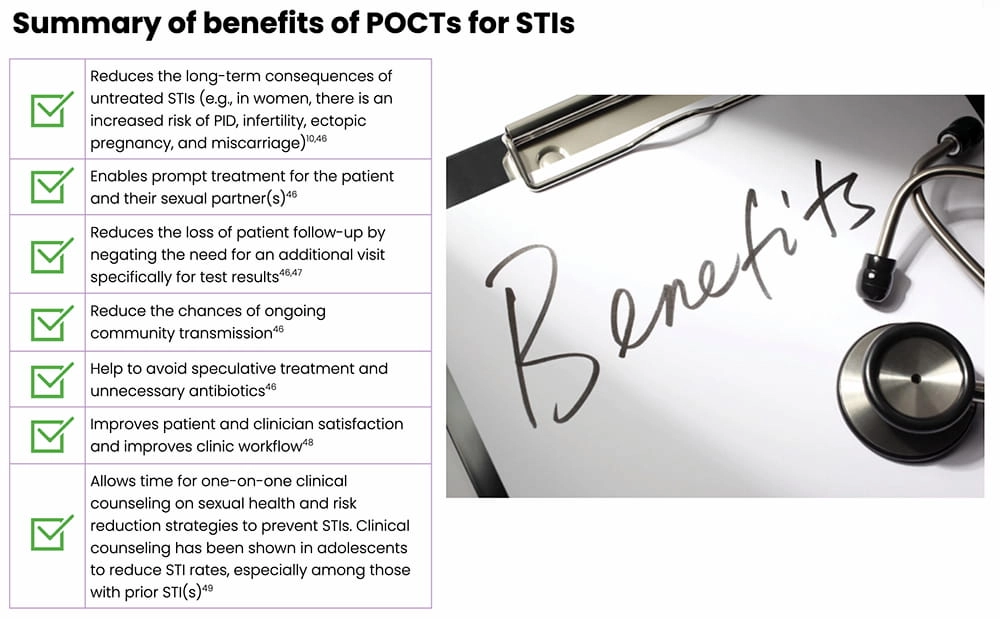

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), simple, rapid, and accurate Point-of-Care tests (POCTs) can greatly improve ST management by allowing a clinician to definitively diagnose and appropriately treat potential STIs.34

Duration of infections

For chlamydia:30

- The duration of untreated asymptomatic chlamydial infections is not known.

- Modeling studies suggest that although men are less likely to establish an infection, they are slower at resolving it. The mean duration of untreated symptomatic infections in males is ~2.84 years compared with ~1.35 years in females.

For trichomoniasis:

- In females, untreated trichomoniasis can persist for months, or even years.35

- In males, infection generally persists for <10 days.36,37

Infertility and untreated STIs

Recall, Tina noted during her medical history that she and her husband have been attempting to get pregnant for over 12 months, which may meet the American Society for Reproductive Medicine guidelines for infertility.4

Among women with infertility, it is estimated that 35% also have a post-inflammatory change to structures in the pelvis that interfere with the function of the fallopian tubes – characteristics of PID.39,40

With Tina’s diagnosis of chlamydia and the presence of cervical motion and uterine and adnexal tenderness, the physician notes ’possible PID’ in Tina’s chart, and encourages her to discuss this with the RE who she is scheduled to visit.

Key Point

The consensus among the medical community is that PID caused by chlamydial infection is the most common preventable cause of tubal factor infertility.40

Infertility, PID, and untreated STIs

C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are the most common causes responsible for the development of PID and are implicated in one-third to one-half of all PID cases.22

The chance of developing tubal factor infertility following a single episode of PID is approximately 10%, and each recurrence of PID subsequently doubles the risk of tubal damage, regardless of whether the patient has symptoms.40

In addition, coinfections intensify inflammation, thus favoring scarring and increased risk of tubal factor infertility.40

This makes it critical that PID is recognized and treated promptly. Routinely screening and treating sexually active women for chlamydia and gonorrhea reduces their risk of PID.5,22,41

Non-STI infectious causes of PID include tuberculosis,Mycoplasma genitalium, and mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections in the pelvis.22,39

Case Update

What if STI Test Results Are Available During the Patient Visit?

Let’s revisit Tina’s story, but see how differently it would play out if the clinic was equipped with a rapid, highly accurate POCT, such as the Visby Medical Sexual Health Test…

- During her clinic visit, the nurse asks Tina to provide a self-collected vaginal swab and urine sample; both samples are processed right away, at the start of the visit.

30 minutes later…1

- Tina meets with the physician who has both her urinalysis and the POCT results.

- The POCT comes back positive for two of the three STIs tested – chlamydia and trichomoniasis.

- The physician provides one-on-one clinical counseling on sexual health, including information on the consequences of untreated STIs and risk reduction strategies to prevent future STIs.1, 42

- Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is discussed as an option for Tina’s sexual partner as a means to prevent re-infections and further transmission.41

Key Point

If this POCT had been used in the clinic, Tina would have promptly received the appropriate treatments for the two STIs, as well as EPT.10

Note: Detection of organisms that cause BV and VVC are not part of the Visby Medical Sexual Health Test; an alternate diagnostic test would be needed for those two infections.

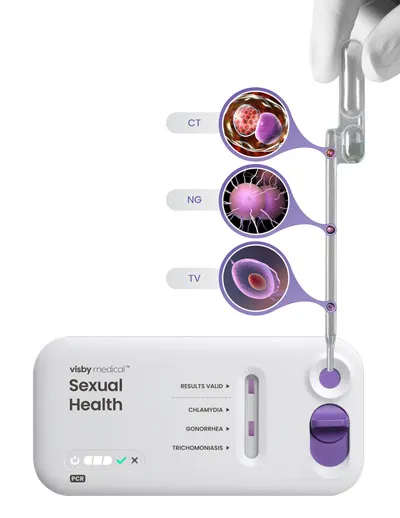

Visby Medical Sexual Health Test

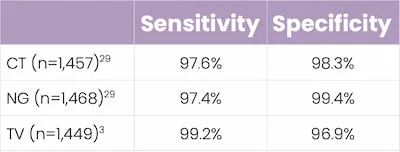

The Visby Medical Sexual Health Test46 is a POCT that enables result-driven, effective treatment delivery during a single clinic visit.

- It takes less than 30 minutes to process results from a patient-collected vaginal swab.

- It is a compact, single-use, disposable, nucleic acid amplification polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can test for and distinguish the genetic material of three pathogens causing chlamydia (CT), gonorrhea (NG), and trichomoniasis (TV).

- In studies, this POCT demonstrated high percent sensitivity and specificity across all three STIs.

Did you know?

Clinical counseling on STIs, including information about risk reduction, contraceptives, and safe sex practices, is an effective means to reduce high-risk STI behaviors in both adolescents and adults.42

A systematic review of 13 meta-analyses (representing 248 studies) found that behavioral counseling aimed at promoting coltdom use was effective in reducing STIs, improving safe sex practices, and providing education on STIs and their prevention.42,45

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) all recommend routine clinical counseling around STI prevention and safe sex practices.42 However, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study showed that this type of counseling was not routine among women aged 15 to 44 years, with only 30% of women reporting a recent conversation with a clinician about STIs.42

Key Takeaways

The Visby Medical Sexual Health Test46 is a POCT that enables result-driven, effective treatment delivery during a single clinic visit.

- Traditional PCR-based STI testing can take several days to return results; in this instance, syndromic management may be used to treat potential STIs.46,48

- Syndromic management of STIs can lead to both under- and overtreatment10

- Inappropriate use of antibiotics comes with risks

- Untreated STIs or failure to appropriately treat STIs increases the risk of complications, especially in women (e.g, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage)10,50

- Point-of-Care testing allows a patient to receive an exam, precise diagnosis, and appropriate treatment all in one clinic visit47,48

- This helps to expedite treatment for both the patient and their sexual partner(s), and reduce community spread43,48,50

Traditional PCR/NAAT vs POCT24,50

References

- Dawkins M, Bishop L, Walker P, et al. Clinical integration of a highly accurate PCR point-of-care test can inform immediate treatment decisions for chlamydia, gonorrhea and trichomonas. Sex Trans Dis. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001586

- A guide to taking a sexual history. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed January 14, 2022.

- Car J. Urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ Learning. 2006;332:94-97.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Fertility evaluation of infertile women: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:1255-1265.

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

- Rubin ES, Rullo J, Tsai P, et al. Best practices in North American pre-clinical medical education in sexual history taking: consensus from the summits in medical education in sexual health. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1414-1425.

- Speck PM, Faugno DK, Mitchell S, Ekroos RA, Hallman MG. Definitions and anatomical review. In: Sexually Transmitted Infection and Disease Assessment: for Health Care Providers and First Responders. STM Learning, Inc.; 2021:1-22.

- Sobel JD, Barbieri RL, Eckler K. Patient education: vaginal discharge in adult women (beyond the basics). UpToDate® website. Updated March 8, 2021.

- Mitchell H. ABC of sexually transmitted infections: vaginal discharge – causes, diagnosis, and treatment. BMJ. 2004;328:1306-1308.

- Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted infections. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Published July 15, 2021. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- Curry A, Williams T, Penny ML. Pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnosis, management, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:357-364.

- Cortes EG, Adamski JJ. Chandelier sign. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2022.

- Syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) website. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- What is a urinalysis (also called a “urine test”)? National Kidney Foundation website. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- HCG in urine. Medline Plus website. Updated February 18, 2022.

- Coleman JS, Gaydos CA. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis: an update. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00342-18.

- Gonorrhea – CDC fact sheet (detailed version). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed July 22, 2021.

- Thuener JE, Clouse AL. Gonorrhea. In: Skolnik NS, Clouse AL, Woodward J eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2nd edn. Humana Press; 2013:61-69.

- 10 ways STDs impact women differently from men. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Issued April 2011. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- Markos AR. Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. In: Markos AR, ed. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2009:37-43.

- STDs & infertility. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed June 22, 2021.

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) – CDC fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed July 22, 2021.

- Owens JN, Skelley JW, Kyle JA. The fungus among us: an antifungal review. US Pharmacist website. Published August 19, 2010. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- Fluconazole. DrugBank website. Updated March 10, 2022.

- Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website. Reviewed March 5, 2021.

- FDA drug safety communication: use of long-term, high-dose Diflucan (fluconazole) during pregnany may be associated with birth defect in infants. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website. Reviewed August 4, 2017.

- Lovett A, Duncan JA. Human immune responses and the natural history of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. Front Immunol. 2019;9:3187.

- Sobel JD, Mitchell C. Trichomoniasis. UpToDate® website. Updated March 8, 2022.

- Garcia MR, Wray AA. Sexually transmitted infections. NCBI StatPearls website. Updated July 15, 2021.

- Hsu K. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. UpToDate® website. Updated September 20, 2021.

- Azithromycin. DrugBank website. Updated March 10, 2022.

- Metronidazole. DrugBank website. Updated March 10, 2022.

- Caruso G, Giammanco A, Virruso R, Fasciana T. Current and future trends in the laboratory diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2021; doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031038

- Clinic-based evaluation of point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of genital chlamydial, gonococcal and trichomonas infection in women presenting with vaginal discharge. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- Trichomoniasis – CDC fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed July 22, 2021.

- Kissinger P. Trichomonas vaginalis: a review of epidemiologic, clinical and treatment issues. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:307.

- Krieger JN. Trichomoniasis in men: old issues and new data. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:83-96.

- Key statistics from the National Survey of Family Growth – I listing. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed June 20, 2017.

- Novy MJ, Eschenbach DA, Witkin SS. Infections as a cause of infertility. Global Library of Women’s Medicine website. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- Lujan A, Fili S, Damiani MT. Female infertility associated to Chlamydia trahomatis infection. In: Darwish AM, ed. Genital Infections and Infertility. IntechOpen; 2016:135-158.

- Phillips AJ. Chlamydia. In: Skolnik NS, Clouse AL, Woodward J eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2nd edn. Humana Press; 2013:39-60.

- Evidence summary: counseling for sexually transmitted infections. Women’s Preventative Services Initiative website. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- Expedited partner therapy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed April 19, 2021.

- Partner treatment for STIs. Guttmacher Institute website. Published March 1, 2022. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- von Sadovszky V, Draudt B, Boch S. A systematic review of reviews of behavioral interventions to promote condom use. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11:107-117.

- Morris SR, Bristow CC, Wierzbicki MR, et al. Performance of a single-use, rapid, point-of-care PCR device for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:668-676.

- Toskin I, Murtagh M, Peeling RW, Blondeel K, Cordero J, Kiarie J. Advancing prevention of sexually transmitted infections through point-of-care testing: target product profiles and landscape analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93:S69-S80.

- Adamson PC, Loeffelholz MJ, Klausner JD. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: a review of recent developments. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:1344-1351.

- In-iw S, Braverman PK, Bates JR, Biro FM. The impact of health education counseling on rate of recurrent sexually transmitted infections in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:481-485.

- Natoli L, Maher L, Shephard M, et al. Point-of-care testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea: implications for clinical practice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100518.