VISBY MEDICAL™ PATIENT CASE STUDY

A case of overtreatment associated with syndromic management of STIs

Case Study #3: Pam

This study is based on a real-life case.1 Some details have been altered to fit the format of this study to preserve the identity of the patient. All photos are stock photos, used for illustrative purposes only. Posed by models.

Case Intro

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Meet Pam

Pam, a divorced 46-year-old woman, presents to the clinic with complaints of malodorous vaginal discharge and itching.

Did you know?

Vaginal discharge, which is comprised of skin cells, bacteria, mucus, and fluid, helps protect the lower female reproductive tract and urinary tract by providing lubrication to the vaginal tissue and protecting against infections.2

Vaginal discharge can be a completely normal finding in women, and the characteristics of normal discharge vary depending on factors such as diet, sexual activity, medication, and stress.3

Normal discharge is typically white or clear, thick, mucus-like, and odorless.2 However, in some cases, normal discharge can also be yellowish, slightly malodorous, and present with mild irritation,3 Medical evaluation is recommended when vaginal discharge presents with any of the following signs and symptoms:2,3

- Itching of the vulva or vagina

- Redness, burning, or swelling of the vulva

- Vulvovaginal erosions

- Cervical or vaginal friability

- Discharge that is malodorous, foamy, green/yellow colored, and/or bloody

- Abdominal or pelvic pain

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Medical and Sexual History

In the exam room, the nurse collects medical and sexual history.2

Pam recounts her symptoms, all of which started approximately I week prior:

- Malodorous, or foul-smelling, vaginal discharge

- Vaginal itching

- Denies any abdominal or pelvic pain

Pam shares that she is sexually active.

She is in perimenopause based on her gynecologist’s assessment after she experienced hot flashes, night sweats, and sporadic and irregular menstrual cycles over the past 3 years.6

The nurse requests a urine sample to assess for signs of a urinary tract infection and to determine pregnancy status.3

Nurse-patient dialogue

Nurse: When did the discharge and itching start and how would you describe it?

Pam: All the signs and symptoms started about 1 week ago. The discharge is foul-smelling, has a thin mucus-like consistency, and is off-white/gray in color. The vaginal itching is persistent and causing some irritation to that area.

Nurse: Are you sexually active? If so, do you have any new sexual partners?4

Pam: Yes. After my divorce, I re-entered the dating scene and have had a few sexual partners in the last few months.

Nurse: If you use pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention methods, which ones do you use and how often do you use them?4

Tina: I stopped taking birth control pills when my (now) ex-husband had a vasectomy following the birth of our second child. Given my age and perimenopausal status, I’m not worried about pregnancy. My partners use condoms most of the time; there were only a handful of times when we didn’t use one.8

Quiz Question #1

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Physical and Pelvic Exams, Lab Assessments

Pam collects the urine sample and prepares for the physician’s physical and pelvic exams.5

Examinations10

Physical Exam

- All vitals are within normal limits

- Patient is alert, well-developed, and well-nourished

Pelvic Exam

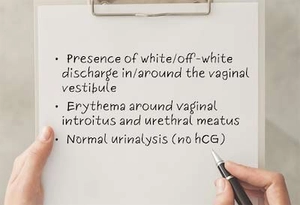

External findings:

- Presence of thin, mucus-like, off-white/gray-colored discharge around the vaginal vestibule. Patient self-reports that it is foul-smelling.

- Noted slight erythema, or redness, of the vulva circumferential to the vaginal introitus. Patient confirms that this is consistent with the location of the itching.

Vaginal swab is collected for lab analysis.

Laboratory Assessments

External lab assessments13,16

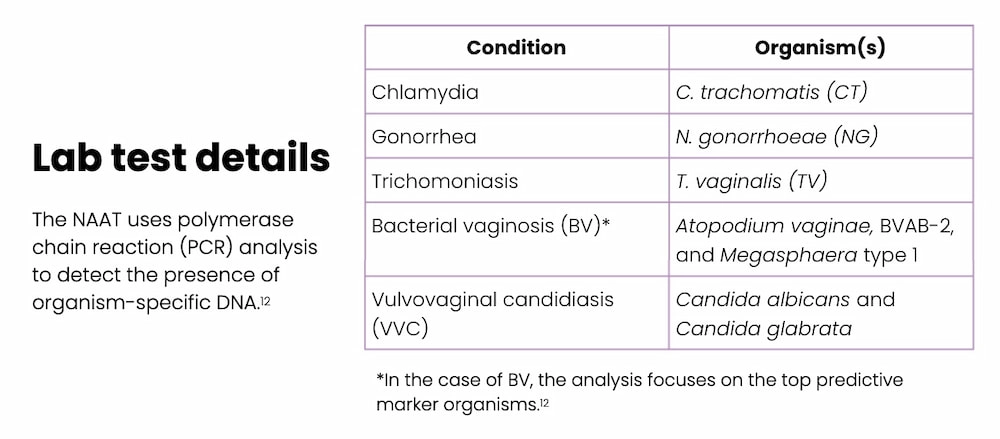

- Vaginal swab is sent to an external lab for a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) to detect the presence of organisms that cause conditions suspected in the differential diagnosis (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis [BV], and vulvovaginal candidiasis [VVC]).1, 11, 12

In-house urine assessment14

External findings:

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG): not detected; negative15

- Visual assessment: clear, straw-colored

- Chemistry assessment: no protein, glucose, or blood detected

Quiz Question #2

Case Update

Day 1 (Clinic Visit): Treatment Plan

The physician reviews his case notes.

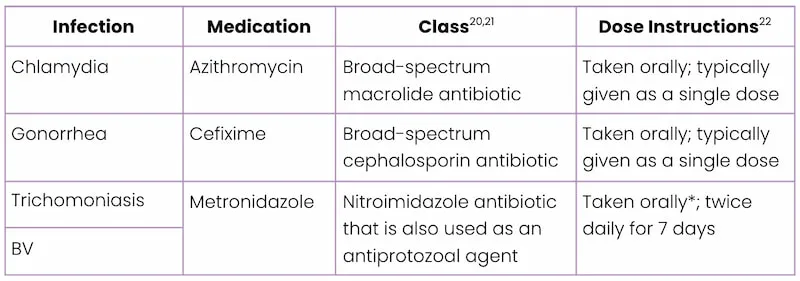

A definitive diagnosis from the lab test will likely not be available for several days, so the physician recommends empirical treatment (syndromic management) targeting the four potential infections shown in the table below.1, 5

*Based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for BV treatment, metronidazole may alternatively be prescribed as a once-daily intravaginal application over a total of 5 days.22 However, intravaginal application is not recommended for trichomoniasis because this route of administration does not permit the drug to reach therapeutic levels in the urethra and perivaginal glands.22

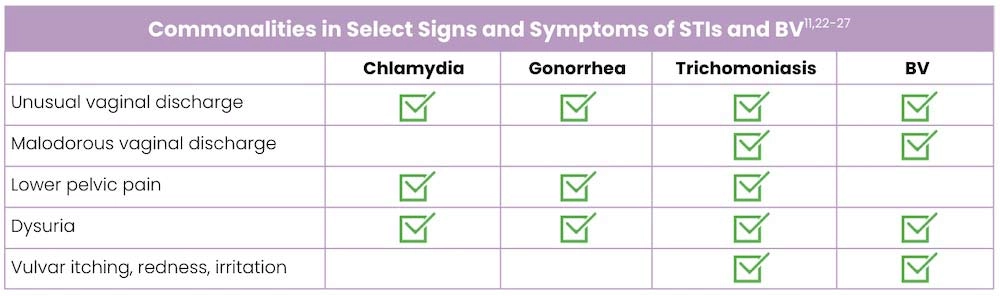

Commonalities Between STIs and BV

Syndromic Management

Syndromic management is a strategy for identifying and treating STIs based only on the specific presenting syndromes, including symptoms identified by the patient and clinically observed signs of infection.10

- It is utilized widely as a means to medically manage people with symptoms of STIs because untreated STIs can cause serious physical complications (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease [PID], infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, preterm delivery, and increased susceptibility to HIV and other STIs) and can impact mental health and relationships with partners.

- In most resource-limited settings, syndromic management is the standard-of-care because laboratory diagnosis is not feasible or results from a lab-based test can take many days.

Racial Disparity and STIs

Black women are disproportionately afflicted by STIs compared with White women.28

The NHANES showed a higher prevalence of trichomoniasis among non-Hispanic Black women compared with non-Hispanic White women.15

- Non-Hispanic White women: 0.81% prevalence

- Non-Hispanic Black women: 9.56% prevalence

In 2018, the CDC estimated that the overall rates of reported chlamydia and gonorrhea cases in Black women were 5 times and 6.9 times greater than the rates reported among White women, respectively.29

The significant racial disparity observed among Black women with STIs is likely multifactorial and may be attributable to:28

- Differential access to quality healthcare or distrust of the healthcare system

- Economic conditions (e.g., inability to afford sexual health services)

- Higher disease prevalence in sexual networks (e.g, in communities with higher rates of STIs, the odds are greater that a local sexual partner is infected)

Quiz Question #3

Case Update

Day 17

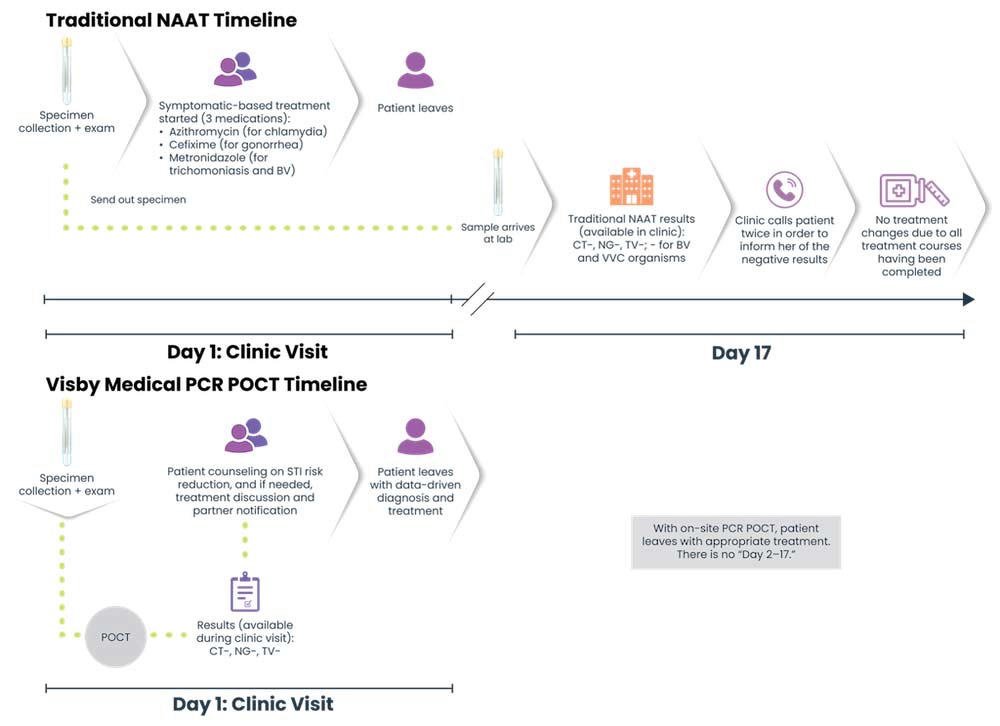

Seventeen days after the initial patient visit, the clinic receives the STI lab results, which have been reviewed by the physician, and confirms that Pam does not have any of the STIs or other infections that were suspected. Nor did she have VVC.

The clinic contacts Pam to inform her of the lab results, and she is told no treatment changes are applicable.30

At this point, Pam has had courses of azithromycin, cefixime, and metronidazole, all of which were not medically necessary in light of the lab results. The physician suspects a noninfectious cause (e.g, a chemical or allergic reaction to soap, detergent, or feminine products).2, 31 Pam is instructed to schedule a follow-up appointment if symptoms persist.5, 22

Key Point

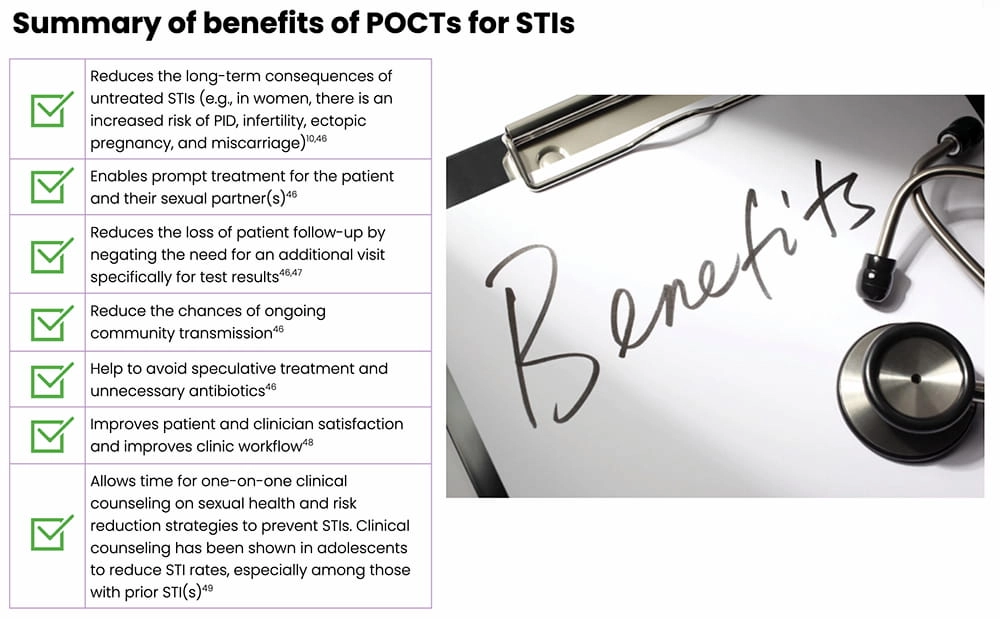

Under syndromic management, the WHO reports that there is considerable overtreatment of women presenting with vaginal discharge with antibiotics. Simple, rapid, and accurate Point-of-Care tests (POCTs) can greatly improve STI management by allowing a clinician to definitively diagnose and appropriately treat potential STIs during the patient visit.33, 34

Implications of Overtreatment

Inappropriate Antibiotic Use

- There is a global surge in antibiotic resistance among bacterial STIs, especially gonorrhea, resulting in limited effective treatment options.5 In fact, over time, gonorrhea has developed resistance to almost all antibiotics that have been used to treat it.35

- Antibiotics, like all medications, come with side effects, including rash, dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, and increased risks of yeast and Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) infections.36 According to the CDC, adverse reactions associated with antibiotic use account for one out of every five medication-related visits to the emergency room.36

- Antibiotic use has been shown to alter the vaginal flora, specifically resulting in the loss of the protective Lactobacillus strains.37 Normally, lactobacilli help maintain an acidic environment to promote their own growth and also help to ward off harmful microbes and viruses by releasing antimicrobial- and viricidal-like compounds.37,38The loss of Lactobacillus strains following antibiotic treatment can result in a less acidic environment that is increasingly susceptible to infections such as BV, VVC and UTIs.37,39

Costs5, 40

- There are costs associated with medications and with treating any subsequent bacterial infection(s) that develop resistance to current recommended therapies (e.g., medical care to address comorbidities and receive additional treatments).

- There are also costs related to the research and development needed to develop novel antibiotic therapies to address the surge in resistance.

Mental Effects Costs1, 5

- Patients treated for or diagnosed with an STI may experience shame, embarrassment, negative stigma, or loss of self-worth.

Case Update

What if STI Test Results Are Available During the Patient Visit?

Let’s revisit Pam’s story, but see how different it would play out if the clinic was equipped with a rapid, highly accurate POCT, such as the Visby Medical Sexual Health Test…34

- During her clinic visit, the nurse asks Pam to provide a self-collected vaginal swab and urine sample; both samples are processed right away, at the start of the visit.1

30 minutes later…1

- Pam meets with the physician who has both her urinalysis and the POCT results.

- The POCT reveals that Pam does not have chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomoniasis.

Key Point

If this POCT had been used in the clinic, Pam would not have received unnecessary treatment for three STIs — chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis — yet she did receive unnecessary treatment under a syndromic management protocol.5,41

Note: Detection of organisms that cause BV and VVC are not part of the Visby Medical Sexual Health Test; an alternate diagnostic test would be needed for those two infections.

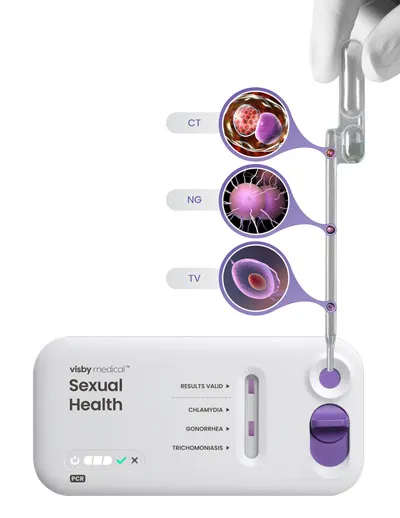

Visby Medical Sexual Health Test

The Visby Medical Sexual Health Test46 is a POCT that enables result-driven, effective treatment delivery during a single clinic visit.

- It takes less than 30 minutes to process results from a patient-collected vaginal swab.

- It is a compact, single-use, disposable, nucleic acid amplification polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can test for and distinguish the genetic material of three pathogens causing chlamydia (CT), gonorrhea (NG), and trichomoniasis (TV).

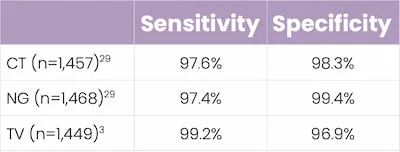

- In studies, this POCT demonstrated high percent sensitivity and specificity across all three STIs.

Key Takeaways

The Visby Medical Sexual Health Test46 is a POCT that enables result-driven, effective treatment delivery during a single clinic visit.

- Traditional PCR-based STI testing (e.g., lab-based NAATs) can take several days to return results; in this instance, syndromic management may be used to treat potential STIs.34,41

- Syndromic management of STIs can lead to both under- and overtreatment5

- The inappropriate use of antibiotics comes with risks.5

- Untreated or failure to appropriately treat STIs increases the risk of complications, especially in women (e.g, PID, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage).5,44

- Point-of-Care testing allows a patient to receive an exam, precise diagnosis, and appropriate treatment all in one clinic visit.

- This helps to expedite treatment for both the patient and their sexual partner(s), and reduce community spread.1, 34, 44

Traditional PCR/NAAT vs POCT21, 44, 35

References

- Dawkins M, Bishop L, Walker P, et al. Clinical integration of a highly accurate PCR point-of-care test can inform immediate treatment decisions for chlamydia, gonorrhea and trichomonas. [published online ahead of print November 22, 2021]. Sex Trans Dis. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001586

- Sobel JD, Barbieri RL, Eckler K. Patient education: vaginal discharge in adult women (beyond the basics). UpToDate® website. Updated March 8, 2021.

- Sobel JD, Barbieri RL, Eckler K. Approach to females with symptoms of vaginitis. UpToDate® website. Updated May 25, 2021.

- A guide to taking a sexual history. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed January 14, 2022.

- Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted infections. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Published July 15, 2021. Accessed January 27, 2022.

- What is menopause? National Institutes of Health (NIH) website. Reviewed September 30, 2021.

- Car J. Urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ Learning. 2006;332:94-97.

- FSRH clinical guideline: contraception for women aged over 40 years. The Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) website/. Amended September 2019.

- Taylor D, James EA. Risks of being sexual in midlife: what we don’t know can hurt us. The Female Patient. 2012;37:17-20.

- Minkin MJ. Sexually transmitted infections and the aging female: placing risks in perspective. Maturitas. 2010;67:114-116.

- Syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) website. Accessed January 31, 2022.

- Coleman JS, Gaydos CA. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis: an update. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00342-18.

- What is a urinalysis (also called a “urine test”)? National Kidney Foundation website. Accessed January 31, 2022.

- HCG in urine. Medline Plus website. Updated January 12, 2022.

- Flagg EW, Meites E, Phillips C, Papp J, Torrone EA. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis among civilian noninstitutionalized male and female population aged 14 to 59 years: United States, 2013 to 2016. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:e93-e96.

- Stemmer SM, Adelson ME, Trama JP, Dorak MT, Mordechai E. Detection rates of Trichomonas vaginalis, in different age groups, using real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:352-357.

- Stemmer SM, Mordechai E, Adelson ME, Gygax SE, Hilbert DW. Trichomonas vaginalis is most frequently detected in women at the age of peri-/premenopause: an unusual pattern for a sexually transmitted pathogen. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:e1-e13.

- Chlamydial infections. National STD Curriculum website. Updated October 15, 2021.

- Gonococcal infections. National STD Curriculum website. National STD Curriculum website. Updated October 3, 2021.

- Azithromycin. DrugBank website. Updated January 31, 2022.

- Metronidazole. DrugBank website. Updated January 31, 2022.

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

- Bacterial vaginosis – CDC fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed January 5, 2022.

- Vaginitis. American Family Physician (AAFP) website. Accessed January 31, 2022.

- Garcia MR, Wray AA. Sexually transmitted infections. NCBI StatPearls website. Updated July 15, 2021.

- Sobel JD, Mitchell C. Trichomoniasis. UpToDate® website. Updated July 22, 2021.

- Bagnall P, Rizzolo D. Bacterial vaginosis: a practical review. JAAPA. 2017;30:15-21.

- STD health equity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed March 2, 2020.

- Health disparities in HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed September 14, 2020.

- Measuring outpatient antibiotic prescribing. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website. Reviewed October 12, 2021.

- Mitchell H. ABC of sexually transmitted infections: vaginal discharge – causes, diagnosis, and treatment. BMJ. 2004;328:1306-1308.

- Caruso G, Giammanco A, Virruso R, Fasciana T. Current and future trends in the laboratory diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2021;8:1038.

- Clinic-based evaluation of point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of genital chlamydial, gonococcal and trichomonas infection in women presenting with vaginal discharge. World Health Organization (WHO) website. Accessed January 31, 2022.

- Morris SR, Bristow CC, Wierzbicki MR, et al. Performance of a single-use, rapid, point-of-care PCR device for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:668-676.

- Bowen VB, Johnson SD, Weston EJ, Bernstein KT. Gonorrhea. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4:1-10.

- Antibiotics use questions and answers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Reviewed October 6, 2021.

- Kurowski K, Ghosh R, Singh SK, Beaman KD. Clarithromycin-induced alterations in vaginal flora. Am J Ther. 2000;7:291-295.

- Joseph RJ, Ser HL, Kuai YH, et al. Finding a balance in the vaginal microbiome: how do we treat and prevent the occurrence of bacterial vaginosis? Antibiotics. 2021;10:1-39.

- Vaginitis. Medline Plus website. Updated October 18, 2021.

- Gupta V, Sharma VK. Syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections: a critical appraisal and the road ahead. Natl Med J India. 2019;32:147-152.

- Adamson PC, Loeffelholz MJ, Klausner JD. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: a review of recent developments. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:1344-1351.

- Toskin I, Murtagh M, Peeling RW, Blondeel K, Cordero J, Kiarie J. Advancing prevention of sexually transmitted infections through point-of-care testing: target product profiles and landscape analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93:S69-S80.

- In-Iw S, Braverman PK, Bates JR, Biro FM. The impact of health education counseling on rate of recurrent sexually transmitted infections in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:481-485.

- Natoli L, Maher L, Shephard M, et al. Point-of-care testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea: implications for clinical practice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100518.

- Cefixime. DrugBank website. Updated January 31, 2022.